Sanatan Dharma, often referred to as Hinduism, is one of the oldest and most complex religions in the world. Its origins date back to prehistoric times, and it has evolved over thousands of years through a rich tapestry of cultural, spiritual, and philosophical developments. This article delves into the origins and evolution of Sanatan Dharma, tracing its journey from ancient times to the present day.

Origins of Sanatan Dharma

1. Pre-Vedic Period (Before 1500 BCE)

The earliest traces of what would later become Sanatan Dharma can be found in the prehistoric cultures of the Indian subcontinent, particularly the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), which flourished around 3300–1300 BCE. This ancient civilization, located in present-day Pakistan and northwest India, was one of the world's earliest urban cultures, known for its advanced architecture, urban planning, and social organization.

Indus Valley Civilization:

Artifacts and Symbols: Archaeological excavations in the Indus Valley have uncovered numerous artifacts that hint at early religious practices. Seals and pottery fragments depict figures in meditative postures, animals, and symbols that may have had religious significance. One of the most famous seals is the "Pashupati Seal," which shows a horned deity surrounded by animals, possibly an early representation of Shiva or a proto-Shiva figure.

Ritual Practices: The discovery of large public baths, such as the Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro, suggests that ritual purification and water-based ceremonies were important aspects of the culture. Additionally, fire altars found at several sites indicate the practice of fire worship, a tradition that would become central to Vedic rituals.

2. Vedic Period (1500–500 BCE)

The Vedic period marks the beginning of recorded history for Sanatan Dharma. This era is named after the Vedas, the oldest and most authoritative scriptures of Hinduism. The Vedic texts were composed in Sanskrit and transmitted orally for centuries before being written down.

The Four Vedas:

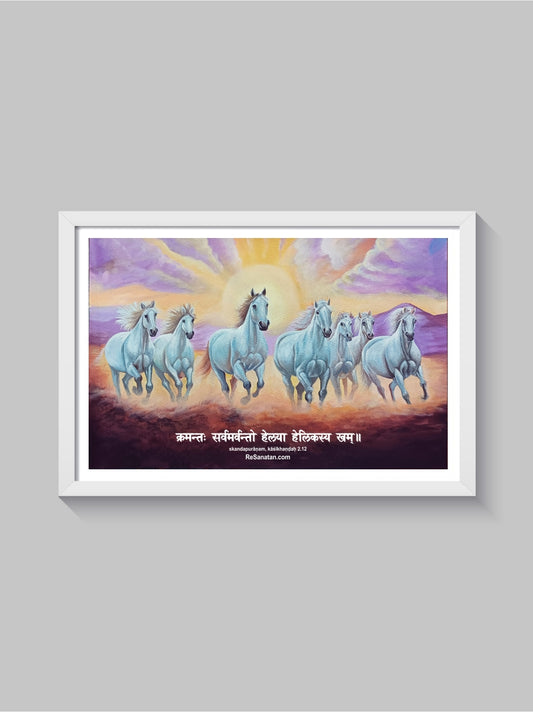

Rigveda: The oldest of the four Vedas, the Rigveda, is a collection of hymns dedicated to various deities such as Agni (fire), Indra (warrior god), and Soma (a ritual drink). These hymns reflect the early Vedic people's reverence for natural forces and their desire to maintain harmony with the cosmos.

Samaveda: The Samaveda consists mainly of hymns borrowed from the Rigveda but set to musical chants. It played a crucial role in the performance of rituals and sacrifices.

Yajurveda: The Yajurveda is a compilation of prose mantras and rituals used in sacrificial ceremonies. It provides detailed instructions for conducting various rituals, highlighting the importance of precise execution to ensure the efficacy of the sacrifices.

Atharvaveda: The Atharvaveda contains hymns, spells, and incantations addressing everyday concerns such as health, prosperity, and protection from evil forces. It reflects a more practical and diverse aspect of Vedic life.

Vedic Deities and Rituals:

Polytheism and Nature Worship: The early Vedic religion was polytheistic, with a pantheon of gods and goddesses associated with natural phenomena and cosmic principles. Deities such as Varuna (god of cosmic order), Vayu (wind god), and Ushas (dawn goddess) were revered and invoked through rituals.

Yajna (Sacrifice): Central to Vedic practice was the yajna or sacrificial ritual, performed by priests (Brahmins) to appease the gods and ensure the prosperity of the community. These rituals involved offerings of ghee, grains, and soma into the sacred fire, accompanied by the chanting of Vedic mantras.

3. Upanishadic Period (800–200 BCE)

The later Vedic period saw a significant shift in the religious and philosophical landscape with the composition of the Upanishads. These texts represent a move away from the ritualistic practices of the earlier Vedic period towards introspective and philosophical inquiry.

Philosophical Inquiry:

Nature of Reality: The Upanishads explore profound questions about the nature of reality, the self (Atman), and the ultimate reality (Brahman). They emphasize the idea that the individual soul (Atman) is identical to the universal soul (Brahman), and realizing this oneness is the path to liberation (moksha).

Karma and Rebirth: The concepts of karma (action and its consequences) and samsara (cycle of birth and death) are central to Upanishadic thought. These ideas introduced the notion that one's actions in this life determine their future existences, leading to the ethical and moral dimensions of Sanatan Dharma.

Key Upanishads:

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad: One of the oldest and most important Upanishads, it delves into the nature of the self and the universe through dialogues and philosophical discussions.

Chandogya Upanishad: This text contains teachings on meditation, ethics, and the nature of reality, including the famous dictum "Tat Tvam Asi" (Thou art that), signifying the unity of the individual soul with the ultimate reality.

Katha Upanishad: Known for its dialogue between Nachiketa and Yama (the god of death), this Upanishad explores the nature of the self, the afterlife, and the path to spiritual knowledge.

Synthesis and Continuity

The evolution of Sanatan Dharma from the pre-Vedic through the Vedic and Upanishadic periods highlights its ability to synthesize diverse cultural and spiritual elements. The transition from the ritualistic practices of the Vedic period to the philosophical and introspective approach of the Upanishads reflects a dynamic tradition that has continuously adapted to changing social and cultural contexts.

The emphasis on eternal principles such as dharma (duty), karma (action), and moksha (liberation) has provided a unifying framework for the diverse beliefs and practices within Sanatan Dharma. This ability to integrate and adapt has allowed Sanatan Dharma to endure and thrive over millennia, influencing countless generations and shaping the spiritual landscape of the Indian subcontinent and beyond.

Evolution of Sanatan Dharma

Sanatan Dharma, or Hinduism, is not a static religion; it has evolved over thousands of years, adapting to social, cultural, and historical changes. Its rich tapestry of beliefs and practices reflects this dynamic process. This article delves into the key phases of its evolution, highlighting the major developments from the Vedic period to modern times.

1. Epic and Puranic Period (500 BCE – 500 CE)

The Epic and Puranic period marked a significant transformation in Sanatan Dharma, characterized by the composition of the great epics—the Mahabharata and the Ramayana—and the Puranas.

The Mahabharata and the Ramayana:

The Mahabharata: This epic, attributed to Vyasa, is one of the longest poems in the world and includes the Bhagavad Gita, a key philosophical text. The Mahabharata narrates the story of the Kurukshetra War, exploring themes of duty, righteousness, and the complexities of human nature. The Bhagavad Gita, a dialogue between Prince Arjuna and Lord Krishna, addresses profound spiritual and ethical dilemmas, emphasizing the importance of dharma (duty) and bhakti (devotion).

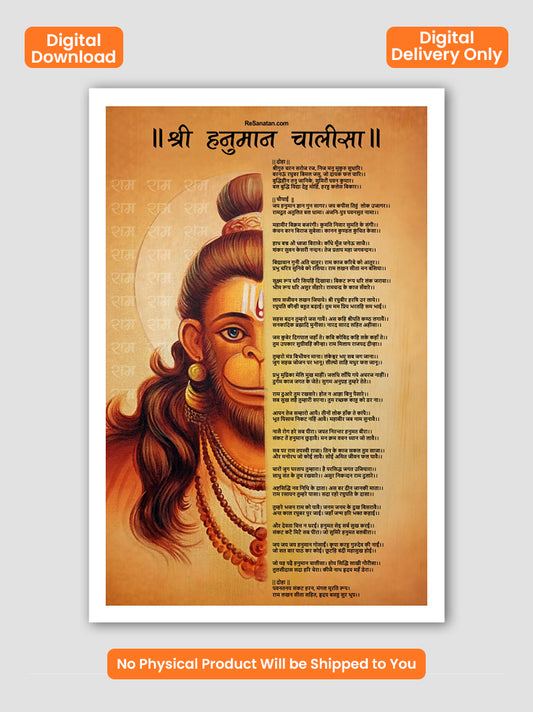

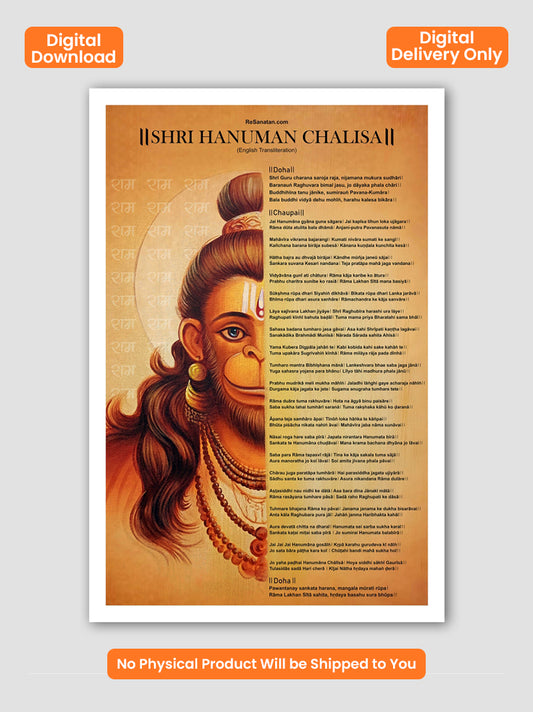

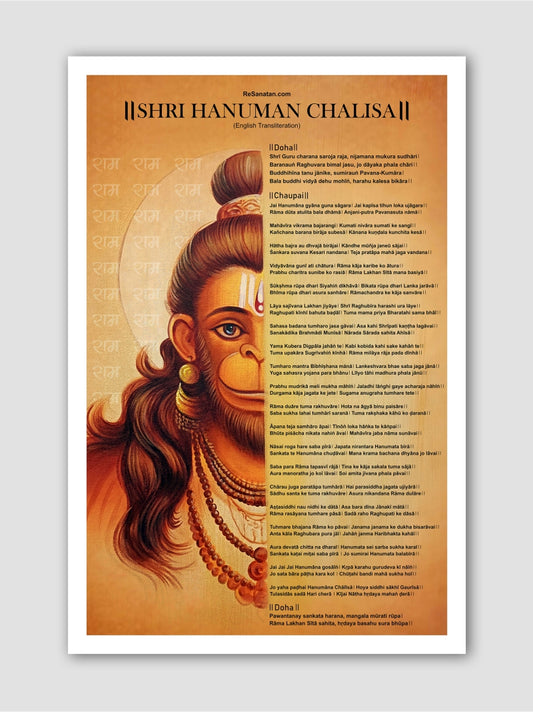

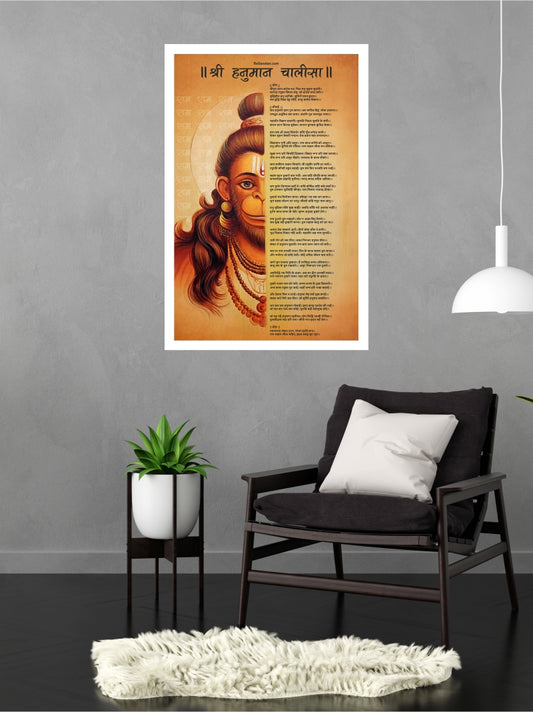

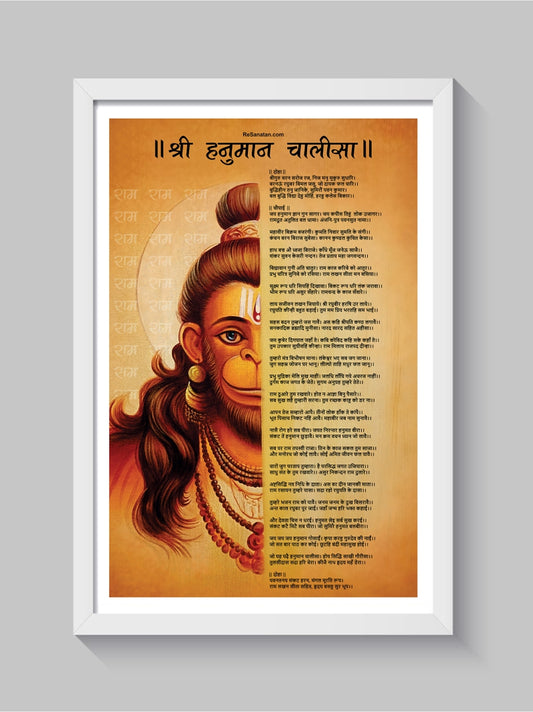

The Ramayana: Attributed to the sage Valmiki, the Ramayana tells the story of Prince Rama, his wife Sita, and his loyal companion Hanuman. This epic highlights ideals of devotion, duty, and the triumph of good over evil. It has had a profound impact on the cultural and religious life of the Indian subcontinent and beyond.

The Puranas:

Mythology and Cosmology: The Puranas are a genre of ancient texts that include myths, legends, and genealogies of gods, heroes, and sages. They provide a cosmological framework and a sacred history that complements the philosophical teachings of the Vedas and Upanishads.

Sectarian Developments: The Puranas played a crucial role in the development of sects within Sanatan Dharma, such as Vaishnavism (devotion to Vishnu), Shaivism (devotion to Shiva), and Shaktism (devotion to the Goddess). These texts emphasize the worship of specific deities and outline various rituals, festivals, and pilgrimages associated with them.

2. Classical Period (500 – 1500 CE)

The Classical period saw the rise of philosophical schools and the development of devotional movements that further enriched Sanatan Dharma.

Philosophical Schools:

Nyaya and Vaisheshika: These schools focus on logic and metaphysics, respectively. Nyaya emphasizes the methods of logical reasoning and epistemology, while Vaisheshika explores the nature of reality through categories such as substance, quality, and motion.

Samkhya and Yoga: Samkhya is a dualistic philosophy that posits the existence of two fundamental realities: Purusha (consciousness) and Prakriti (matter). Yoga, as outlined in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, provides a practical path to achieve spiritual liberation through physical, mental, and spiritual practices.

Mimamsa and Vedanta: Mimamsa focuses on the interpretation of Vedic rituals and the authority of the Vedas. Vedanta, especially the Advaita Vedanta school founded by Adi Shankaracharya, emphasizes non-dualism and the oneness of Atman (self) and Brahman (ultimate reality).

Bhakti Movement:

Devotional Practices: The Bhakti movement emphasized personal devotion to a chosen deity, transcending ritualistic practices and caste distinctions. Devotees expressed their love and surrender through poetry, music, and dance.

Saints and Poets: Prominent saints and poets, such as Kabir, Mirabai, Tulsidas, and Ramanuja, played a pivotal role in spreading the message of bhakti. Their works continue to inspire millions and underscore the accessibility of divine grace to all, irrespective of social status.

3. Medieval Period (1500 – 1800 CE)

During the medieval period, Sanatan Dharma encountered significant challenges and transformations due to foreign invasions and the rise of other religious traditions.

Interactions with Islam:

Sufi Influence: The Sufi tradition within Islam, with its emphasis on mystical experience and devotion, found resonance with the Bhakti movement. This interaction fostered a spirit of tolerance and syncretism, leading to the creation of unique cultural and spiritual expressions.

Conflict and Coexistence: While there were periods of conflict and persecution, many Hindu and Muslim communities found ways to coexist, contributing to a rich and diverse cultural tapestry.

Rise of Regional Traditions:

South Indian Bhakti: The Alvars and Nayanars, poet-saints from Tamil Nadu, emphasized devotion to Vishnu and Shiva, respectively. Their hymns and devotional songs, collected in the Divya Prabandham and Tevaram, played a crucial role in shaping the religious landscape of South India.

Varkari Tradition: In Maharashtra, the Varkari tradition, centered around the worship of Vithoba (a form of Vishnu), emerged. Saints like Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram, and Namdev emphasized devotion, community service, and the chanting of God's name.

4. Modern Period (1800 – Present)

The modern period of Sanatan Dharma has been characterized by reform movements, global dissemination, and renewed interest in its ancient texts and practices.

Reform Movements:

Brahmo Samaj: Founded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy in 1828, the Brahmo Samaj sought to reform Hindu society by promoting monotheism, rationalism, and social reforms such as the abolition of sati and child marriage.

Arya Samaj: Founded by Swami Dayananda Saraswati in 1875, the Arya Samaj emphasized a return to the teachings of the Vedas, rejecting idol worship, and promoting social reforms such as women's education and the eradication of caste discrimination.

Global Dissemination:

Swami Vivekananda: A key figure in the global spread of Sanatan Dharma, Swami Vivekananda's participation in the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago in 1893 brought Hindu philosophy and spirituality to an international audience. He emphasized the universal and inclusive nature of Sanatan Dharma.

International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON): Founded by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada in 1966, ISKCON played a significant role in popularizing Vaishnavism and the practice of bhakti yoga around the world.

Modern Thinkers and Leaders:

Mahatma Gandhi: Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence (ahimsa) and his emphasis on truth (satya) and self-discipline (brahmacharya) were deeply rooted in Hindu principles. His leadership in India’s independence movement and his ethical teachings have had a lasting impact.

Sri Aurobindo and the Mother: Sri Aurobindo's Integral Yoga and the establishment of Auroville by the Mother (Mirra Alfassa) have contributed to the global understanding and practice of Sanatan Dharma’s spiritual teachings.

Key Concepts and Practices of Sanatan Dharma

Sanatan Dharma, commonly known as Hinduism, is characterized by a vast and intricate tapestry of beliefs, rituals, and practices that have evolved over millennia. Central to this ancient tradition are several key concepts that form the foundation of its philosophy and guide the lives of its adherents. This article explores these essential concepts and the diverse practices that bring them to life.

Key Concepts

1. Dharma (Righteousness/Duty):

Definition: Dharma is the moral law governing individual conduct and is considered essential for maintaining order and harmony in society and the universe.

Types of Dharma:

Sva-Dharma: One's personal duty, which varies according to their age, caste, gender, and occupation.

Sanatana-Dharma: The eternal and universal principles that apply to all beings, transcending individual duties.

Role in Life: Adhering to one's dharma is seen as crucial for spiritual growth and societal stability. It encompasses duties to family, society, and the divine, encouraging individuals to act in ways that uphold truth and justice.

2. Karma (Action and Its Consequences):

Law of Cause and Effect: Karma refers to the principle that every action has consequences, which can manifest in this life or future lives. Good actions lead to positive outcomes, while bad actions result in negative consequences.

Types of Karma:

Sanchita Karma: Accumulated past actions that have yet to bear fruit.

Prarabdha Karma: Part of sanchita karma that is currently being experienced in this lifetime.

Agami Karma: Actions performed in the present that will influence future outcomes.

Moral Implications: Understanding karma encourages individuals to live ethically, as their actions directly impact their spiritual progression and future circumstances.

3. Moksha (Liberation):

Ultimate Goal: Moksha is the liberation from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara). It represents the union of the individual soul (Atman) with the supreme reality (Brahman).

Paths to Moksha: Different paths or yogas are prescribed for achieving liberation:

Jnana Yoga: The path of knowledge and wisdom.

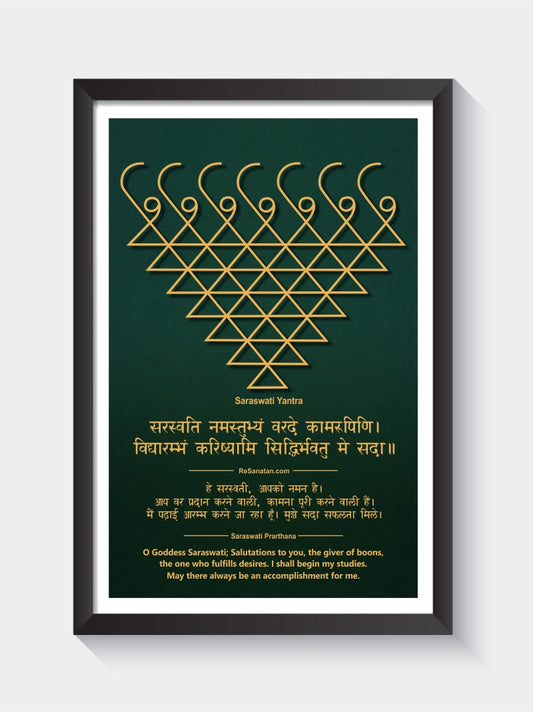

Bhakti Yoga: The path of devotion and love for a personal deity.

Karma Yoga: The path of selfless action and service.

Raja Yoga: The path of meditation and discipline.

State of Realization: Moksha is attained through the realization of the true nature of the self and the universe, leading to eternal bliss and freedom from suffering.

4. Atman and Brahman:

Atman: The individual soul or self, considered eternal and indestructible.

Brahman: The ultimate, unchanging reality, beyond the physical universe, which is the source of all existence.

Unity of Atman and Brahman: The Upanishadic teaching "Tat Tvam Asi" (Thou art that) encapsulates the idea that the individual soul is fundamentally one with the universal soul. Realizing this oneness is key to spiritual enlightenment.

Key Practices

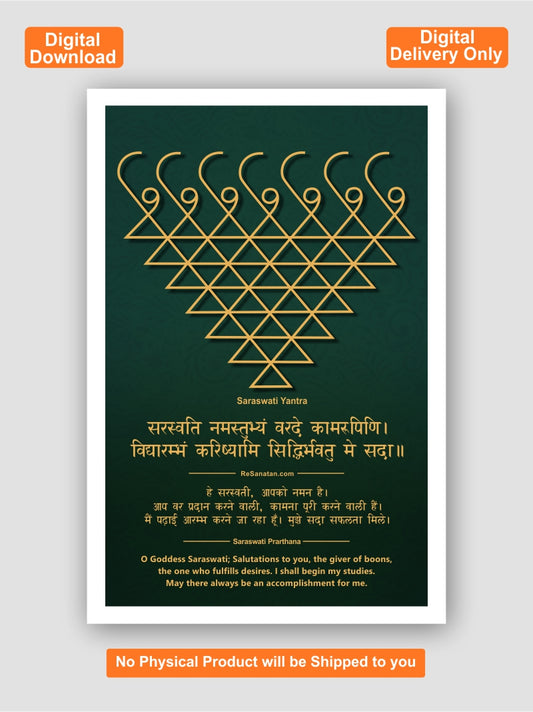

1. Puja (Worship):

Daily Worship: Puja involves offerings of flowers, food, incense, and prayers to deities at home or in temples. It is a way to express devotion and seek blessings.

Elements of Puja: Includes invoking the deity, offering a seat, washing the deity's feet, offering water, clothing, and food, and performing arati (waving of lights).

Types of Puja:

Nitya Puja: Daily worship performed at home.

Naimittika Puja: Special worship performed on specific occasions and festivals.

Kamya Puja: Worship performed to fulfill specific desires or requests.

2. Yoga and Meditation:

Ashtanga Yoga: The eightfold path of yoga outlined by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras, which includes ethical guidelines (Yama and Niyama), physical postures (Asanas), breath control (Pranayama), sensory withdrawal (Pratyahara), concentration (Dharana), meditation (Dhyana), and ultimate absorption (Samadhi).

Meditation Practices: Techniques such as mantra repetition, visualization, and mindfulness are used to calm the mind and attain spiritual insight.

3. Festivals and Celebrations:

Diwali: The festival of lights, celebrating the victory of light over darkness and good over evil.

Holi: The festival of colors, celebrating the arrival of spring and the playful spirit of Krishna.

Navaratri: A nine-night festival dedicated to the worship of the Goddess in her various forms.

Durga Puja: Celebrating the victory of Goddess Durga over the buffalo demon Mahishasura.

Rituals and Community: Festivals are marked by rituals, prayers, fasting, feasting, and communal gatherings, reinforcing cultural and spiritual values.

4. Pilgrimages:

Sacred Sites: Pilgrimages to holy places such as Varanasi, Rameswaram, Kedarnath, and the Char Dham sites are considered highly meritorious.

Kumbh Mela: The largest religious gathering in the world, held every 12 years at four different locations, where devotees take a holy dip in sacred rivers.

Significance: Pilgrimages provide opportunities for spiritual purification, penance, and devotion.

5. Rites of Passage:

Samskaras: Life-cycle rituals that mark important stages in an individual’s life, from birth to death. Key samskaras include:

Namakarana: Naming ceremony for a newborn.

Upanayana: The sacred thread ceremony, marking the initiation of a young boy into Vedic studies.

Vivaha: Marriage ceremony, a sacred union of two individuals.

Antyeshti: Funeral rites, ensuring the soul’s journey to the afterlife.

6. Ethical and Social Practices:

Ahimsa: The principle of non-violence, which underpins ethical conduct and compassion towards all living beings.

Satya: Adherence to truth and honesty in thought, word, and deed.

Dana: The practice of giving and charity, promoting generosity and social responsibility.

Seva: Selfless service to others, seen as a way to serve God and humanity.

Conclusion

Sanatan Dharma, with its profound spiritual insights and diverse practices, continues to be a source of inspiration and guidance for millions of people worldwide. Its emphasis on universal values such as truth, non-violence, compassion, and respect for all beings has made it a timeless and enduring tradition. As it evolves and adapts to the changing times, Sanatan Dharma remains a testament to the resilience and wisdom of an ancient civilization that continues to thrive in the modern world.